oto

takenPhoto

taken during our Oct. 2012 reunion held in

Columbus, Georgia during our Oct. 2012 rPhoto eunion held in

Columbus, GeorgiaPhoto

taken during our Oct. 2012 reunion held in

Columbus, Georg

oto

takenPhoto

taken during our Oct. 2012 reunion held in

Columbus, Georgia during our Oct. 2012 rPhoto eunion held in

Columbus, GeorgiaPhoto

taken during our Oct. 2012 reunion held in

Columbus, Georg

Photo taken at our 2012 Columbus, Georgia Reunion

Ph oto

takenPhoto

taken during our Oct. 2012 reunion held in

Columbus, Georgia during our Oct. 2012 rPhoto eunion held in

Columbus, GeorgiaPhoto

taken during our Oct. 2012 reunion held in

Columbus, Georg

oto

takenPhoto

taken during our Oct. 2012 reunion held in

Columbus, Georgia during our Oct. 2012 rPhoto eunion held in

Columbus, GeorgiaPhoto

taken during our Oct. 2012 reunion held in

Columbus, Georg

The following article was written by Mr. Charles L. Westmoreland and appeared in the Nov. 16, 2007 edition of The News Standard of Meade County, Kentucky.

The News Standard

Straightforward • Steadfast • Solid

![]()

Honoring our Heroes

Veterans Day — Nov. 11, 2007

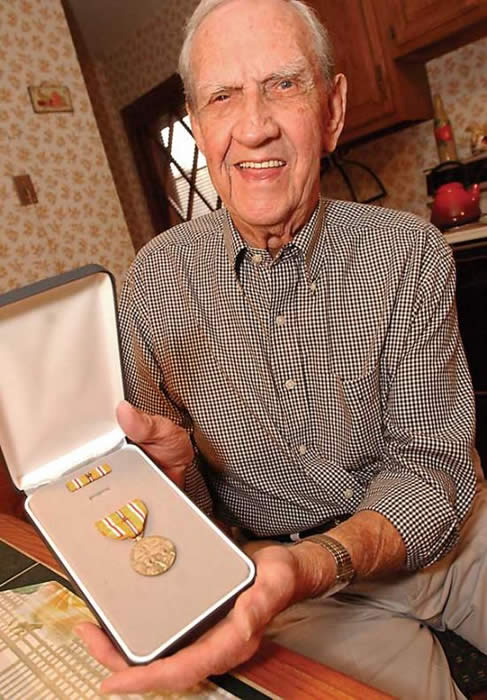

Local veteran receives WWII medal for service more than 60 years ago

By Charles L. Westmoreland

editor@thenewsstandard.com

The surprise Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor in late 1941 ripped through the nation, spurring the United States’ involvement in World War II while also motivating tens of thousands of Americans to enlist in the military for the sake of world preservation. Brandenburg resident Romeo Costantine was one of those men. He enlisted in the Air Force as an aircraft mechanic two months after the attack and soon after was deployed to the South Pacific. But it wasn’t until last month that Costantine was fully-recognized for his service in the “war to end all wars.”

Costantine, 86, was awarded the Asiatic-Pacific Campaign Medal with Bronze Star Attachment Oct. 5 during a ceremony in St. Louis, Mo. for his service in the Pacific theatre in 1944 with the 46th Troop Carrier Squadron, 317th Troop Carrier Group (TCG), also known as the “Jungle Skippers.” About 70 of his brethren who served in the 317th TCG during WWII and after also received the medal.

Costantine said his 22 months of service in the Pacific was never about glory or medals — it was something much deeper.

“I love my country and I would have done anything to keep it free and keep the rights of everyone here,” he said. “When you hear of someone far away being persecuted, I would serve any amount of time to secure the rights of those people.

“Receiving that medal was nice and we enjoyed it. After 64 years, we finally got that one.”

Costantine flew on C-47 Skytrains and a variety of other aircrafts that delivered supplies to the front lines and dropped off paratroopers, while also evacuating wounded troops when needed. He had a dangerous job, which was evident by the amount of repairs he would make to his aircraft.

Once, Costantine spent all night repairing 143 bullet holes in his aircraft so it could fly the next morning.

“The flying crews had most of the danger,” he said. “When we first went over, we were short on airplanes and you only had a crew chief and an assistant crew chief. We had to fly every other day and we had to maintain our airplanes. A lot of times, we’d have to stay overnight and sleep on the airplane when we were away from base.”

Costantine also was awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross and Air Medal (with oak leaf attachment) among other awards. During his service, Costantine logged nearly 1300 hours of flight time. In 2003, he was made an honorary colonel of the 5th Air Force.

Col. Kevin Jackson, Commander of the 317th Airlift Group based at Dyess Air Force Base, Texas, awarded Costantine and the other veterans the medal during a ceremony at Scott Air Force Base. The ceremony was part of the 317th Airlift Group’s annual reunion.

Jackson said the drawdown in troops after World War II was quick and sometimes paperwork for the awards didn’t follow veterans when their service ended.

“There are efforts to clean up those shortfalls so we can award the medals these gentlemen so dearly earned,” he said.

Jackson, who was also a guest speaker at October’s reunion, called Costantine’s generation a “living heritage” for his unit and it was an honor to present the medals.

“(The veterans) think what we’re doing today is amazing and today’s aviators are in awe of what they did,” he said. “Today the technology we have is spellbinding compared to what these gentlemen had to deal with. They come from a different time and a different era. When we mobilized in WWII, there was a unity and closeness in this nation we’ve never known to this day.”

He referred to the bond between today’s generation of airmen and Costantine’s generation as “instantaneous brotherhood.”

“What’s neat about our organization is if your in the 317th you’re a member for life,” he said. “It doesn’t matter when you wore the patch or how old you are, we’re all brothers-in-arms. I feel honored and privileged to have a veterans organization as strong as what we have.”

Costantine enlisted in the Air Force out of Clarksville, W.Va., before spending time at several state-side installations including Bowman Field in Louisville and Fort Benning, Ga. He left the Air Force as a Tech Sergeant after 44 months of service, but said the bonds formed between him and his comrades will last forever. “We were a close-knit bunch,” he said. “We were just like brothers, and when we received replacements we adopted them, too.”

Unfortunately, not all of Costantine’s brothers-in arms made it back to the states. His unit experienced a heavy loss when 40 of 41 servicemen aboard a B-17C were killed when the aircraft crashed at Bakers Creek in Australia. Costantine was supposed to be on that flight.

“They woke me up and told me I wouldn’t be going and someone else took my place,” he said. “We still don’t know what happened.”

His best friend, Dale Curtis, was on board. Costantine’s youngest son, Jeff, 57, was given the middle name Dale in honor of his father’s friend.

Jeff, along with his older brother, Bruce, 59, a Vietnam War veteran, and their mother and Romeo’s wife of 62 years, Alice, 84, were in attendance at the ceremony last month.

The annual reunions are a family affair for the Costantines. Romeo Costantine organized reunions in Louisville

for the 46th Troop Carrier Squadron until two years ago when the number of members became to low, deciding instead to merged with the 317th TCG’s veterans group.

“It was an honor,” Jeff Costantine said of watching his father receive the medal. “I wouldn’t have missed it for the world. Just to see his face and get that recognition, albeit 60 years later, was a special moment.

“My dad never really talked a lot about World War II and it wasn’t until these reunions that we got to find out what he did. These guys were fascinating. They must have had a Spartan-like conditioning to do what they did. I still say they are the greatest generation for what they had to do.”

The following article appeared in the Nov. 5th 2007 edition of the Addison County Independent and is reproduced here with permission of the writer Mr. John Flowers.Obituari

LIFE-LONG MIDDLEBURY resident Charlie Novak was presented on Sunday with a belated bronze service star in recognition of his service in the Pacific during World War II.

Independent photo/Trent Campbell

November 1, 2007

By JOHN FLOWERS

MIDDLEBURY — It was 62 years ago that an Army medic all but laughed at the notion of recommending Charlie Novak for a Purple Heart for a shoulder wound he received in 1945 during an air raid on the island of Leyte in the Philippines during World War II.

Novak, a Middlebury native, never really felt slighted by the medic’s actions.

“I kind of got a kick out of it,” Novak, now 86, said last week.

Well, the United States government last month made up for any shortchanging of recognition for Novak and more than 70 soldiers who served with him in the 317th Troop Carrier Group of the U.S. Army Air Force. In a belated move that has yet to be fully explained, the U.S. military last month awarded Novak and his comrades the Asiatic Pacific Campaign Medal with Bronze Service Star Attachment, in recognition of their actions during WWII in the Pacific.

Gov. James Douglas formally presented Novak with the award, along with two other medals, at a special ceremony at the Middlebury American Legion headquarters on Wilson Road on Sunday, Oct. 28.

“I’m very proud,” Novak said, his voice brimming with emotion as he looked down at the shiny medal that was more than a half-century overdue.

“I have some good memories, but also some bad memories, because a lot of good guys were killed,” he said.

His military journey began in 1941 in a rather unconventional fashion.

Novak, then 19, had taken a job in Springfield with Johnson Lampson, a manufacturer of drill machines and turret lathes. Novak was assigned the job of drilling holes into the components that were assembled into the turret lathes.

He worked 12 hours per day for seven-day stretches (with the ensuing two days off) at what was then a very nice wage of 50 cents per hour.

After three months on the job, Novak decided to take a day off. He had a date for the junior prom. It proved to be a very costly outing.

“When I went back to work the next day, I found out I’d been fired,” Novak said.

When his employer tried to negotiate terms for his rehiring, Novak told him where he could stick the job.

“I said, ‘You can’t make me do anything I don’t want to do,’” Novak recalled. “I said, ‘I never liked Springfield anyway.’”

He decided that day to make a dramatic change in his line of work.

“On my way home, I stopped in Rutland to talk to a military recruiter,” Novak said.

He knew he would likely face a substantial hurdle in being accepted. That’s because Novak a few years prior had lost four fingers on his right hand in a printing press accident at the old Middlebury Register newspaper.

Thankfully, Uncle Sam — and his recruiters and physicians in Rutland — knew that Novak was up to the challenge in spite of his missing fingers.

“The doctor asked me if I could fire a gun,” Novak said. “I said, ‘Yes.’ He said, ‘If you can fire a gun and pass the physical, you’re in.’”

He did, and found himself whisked away to Fort Devins, in Massachusetts, for basic training. It was there that he was assigned to the U.S. Army Air Force, which required additional training in Atlantic City, N.J.; Chanute Field in Illinois; and Maxton Air Force Base (AFB) in North Carolina. During these stops, Novak was taught how to rig parachutes and repair airplanes, among other things.

It was at Maxton AFB that Novak and others were organized into the 40th Troop Carrier squadron of the 317th Troop Carrier Group. He went on to military installations in Bowling Green, Ky., and San Francisco before shipping out to the Pacific.

By this time, Japanese forces had attacked Pearl Harbor (Dec. 7, 1941), ushering the United States into WWII. So it was with a sense of anticipation and anxiety that Novak and his mates set to sea.

“We didn’t know where we were going,” Novak said. “We were told nothing.”

The troops spent 30 days on the high seas in an army transport ship, escorted by a cruiser and a destroyer.

“I was (seasick) for six or seven days,” Novak said. “I couldn’t eat.”

He would eat later on — and in style. While most other soldiers were eating nasty eggs, Novak got leftovers from the officer’s mess, because he took a job washing dishes.

“It was seventh heaven,” Novak said with a smile.

After a couple of weeks at sea, the soldiers finally solved the mystery of their imminent destination.

“We got to the Great Barrier Reef, and then we knew we were going to Australia,” Novak recalled.

The 40th joined around 150,000 other troops that had amassed near the community of Townsville in Queensland, Australia. Novak and his crew spent several months at the base, eating, drinking, sleeping and waiting for supplies to arrive, while training for the rough days that lay ahead.

“It was ungodly hot; horrible,” Novak said, though he acknowledged the soldiers were kept well-fed. They had ready access to beef and drink.

“We ate meat three times a day,” Novak said. “We ate and ate.”

The war hit home for Novak and the 40th when they were finally sent to Port Moresby in Papua, New Guinea, in 1944.

“Then we really got into it,” Novak said of U.S. contact with Japanese forces, who had established bases in Papua New Guinea and small islands throughout the Pacific.

Novak was made a crew chief, specializing in repairs to the C-47 Skytrain airplane, which would become key in transporting troops and equipment to combat zones during WWII. He would also occasionally fly on the planes as they “hopped” from island to island — hence the 317th Troop Carrier Group’s nickname of “jungle skippers.”

“We transported paratroopers, handled bombs — anything that was required, because everything was done by plane or boat over there,” Novak recalled. “Island hopping was the prevalent thing. If you couldn’t do it by air, you did it by the water.”

In essence, Novak and his fellow soldiers began carrying through the strategy of Gen. Douglas MacArthur: Bypass an occupied island, hit the next, bypass another, hit the next, thereby taking the battle to some of the enemy while cutting off supplies to the rest.

“He would starve them out,” Novak said of MacArthur’s plan.

The Skytrains and their pilots, at tremendous risk, dropped troops and supplies on remote battlefields to eventually break the backs of the enemy.

“We hit just about every island — Dutch New Guinea, Guadalcanal, Corregidor, Okinawa — everywhere,” Novak recalled. “You moved with the force. You saw all the country you wanted, and then some.”

It was Novak’s job to make sure the Skytrains would stay in the air. Worn engine parts were replaced; 100-hour inspections were performed; bullet holes were plugged; and fluids were leveled off.

“Everyone had to work together,” Novak said.

Soldiers not only worked together, but also had to be self-reliant.

“All you had for protection was a .45 or a rifle,” Novak said. “You were on your own.”

And being a jungle skipper mechanic did not ensure a great measure of safety. Charlie Novak was on the island of Leyte in the Philippines during an air raid 1945.

“There was vicious gunfire,” Novak recalled.

Before he could find cover, Novak was hit in the shoulder by a hunk of shrapnel. Though he was bleeding, the Army medic who examined him wasn’t keen on putting him up for a Purple Heart.

“The medic mocked me,” Novak said. “He never put (mention of the injury) in my records.”

While Novak may never get his Purple Heart, he did get his Bronze Service Star, along with a Vermont Veterans Medal and a Vermont Distinguished Service Medal from Gov. Douglas on Oct. 28. Observers said it was an emotional ceremony.

Novak’s niece, Jean Hadley, attended a special Oct. 5 ceremony at Scott Air Force Base in St. Louis to receive the Bronze Service Star on her uncle’s behalf.

Hadley, who grew up in Middlebury but now lives in Connecticut, is also very emotional about the award and what it means not only to her uncle, but for what it symbolizes for all those who served in WWII.

“It certainly opened my mind to what patriotism is all about,” Hadley said. “People don’t realize what those guys went through. If they think freedom comes cheap, they are very mistaken.”

The Addison Independent

58 Maple Street

P.O. Box 31

Middlebury, VT 05753

802-388-4944

news@addisonindependent.com